HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES Archive

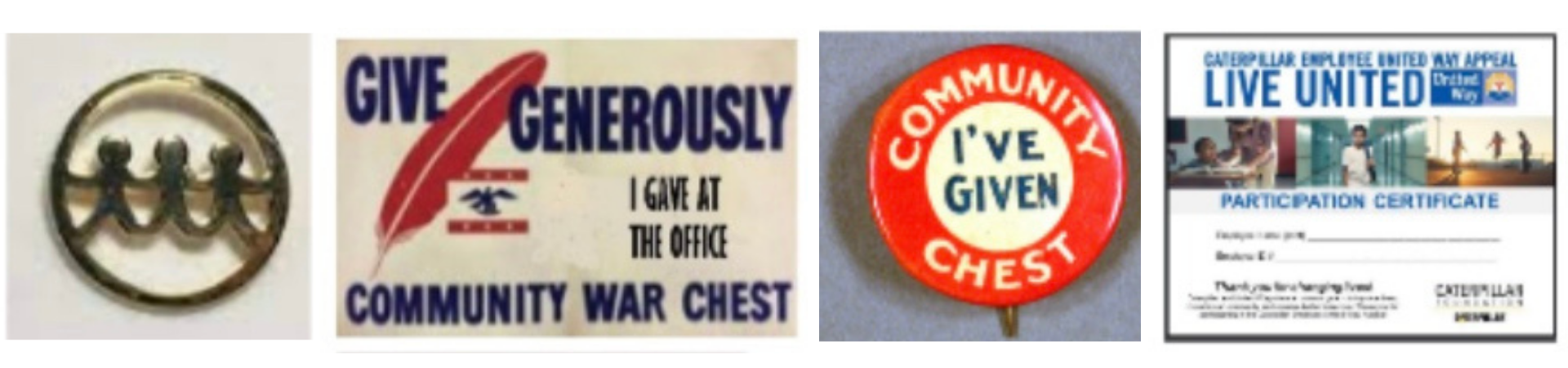

Adaptability – a hallmark of United Way fund-raising success. Practices “THEN” and “NOW” respond to the times.

Author: Dick Aft, United Way Historian and Emeritus Board Member

April, 2024

Change has been a hallmark of the environment in which United Way raised money from its beginnings. Today, more than any other time in the movement’s history, a perfect storm of change has brought about more variety in local approaches to fund-raising than it has since the early 20th century. The COVID-induced changes in many workplaces, on top of changes in generational giving interests, electronics and external pledge processing, has sparked a wide variety of local United Way adaptations. “Uniformity” describes local fund-raising during the 1900’s. THEN, goal setting, fall campaigns, events, promotion, personnel, and data management were done uniformly by nearly every local United Way organization regardless of location or size. NOW, variety defines local experimentation to identify “best practices” that may become the “new normal” elements of United Way fund-raising.

THEN: The nearly universal 20th century fund-raising practices of most local United Way organizations are of more historical interest than current relevance. They do, however, illustrate United Way responsiveness to the fund-raising environment of the times.

Author: Dick Aft, United Way Historian and Emeritus Board Member

April, 2024

Change has been a hallmark of the environment in which United Way raised money from its beginnings. Today, more than any other time in the movement’s history, a perfect storm of change has brought about more variety in local approaches to fund-raising than it has since the early 20th century. The COVID-induced changes in many workplaces, on top of changes in generational giving interests, electronics and external pledge processing, has sparked a wide variety of local United Way adaptations. “Uniformity” describes local fund-raising during the 1900’s. THEN, goal setting, fall campaigns, events, promotion, personnel, and data management were done uniformly by nearly every local United Way organization regardless of location or size. NOW, variety defines local experimentation to identify “best practices” that may become the “new normal” elements of United Way fund-raising.

THEN: The nearly universal 20th century fund-raising practices of most local United Way organizations are of more historical interest than current relevance. They do, however, illustrate United Way responsiveness to the fund-raising environment of the times.

|

The “Monroe High Speed Adding Calculator” machine symbolizes fund-raising back then. How else could the percentage of each campaign division’s goal achievement be quickly calculated as volunteers and corporate campaign chairs streamed into weekly report meetings, dropping their cash and pledge card-filled report envelopes on a table just inside the door? There, nimble-fingered staff members calculated percentages of goal achievement and entered numbers into pre-typed meeting scripts. United Way centerpieces adorned ballroom tables. Campaign leaders sat on elevated platforms. Near the head table, thermometer-filled “scoreboards” reflected the percentage of goal attainment. Woe be to that division volunteer whose team members’ “report envelopes” didn’t contain enough pledge cards and cash to raise their division’s goal attainment to an applause-earning level!

|

|

“OCT 12, 1972, United Way Scoreboard Kept up to Date Dawn Wilkins, a cheerleader at Highland High School, Adams County, places small paper football on chart to indicate progress made by various solicitation divisions in the Mile High United Way fund-raising campaign. She was one of several cheerleaders from two high schools participating in the report meeting Wednesday at the Cosmopolitan Hotel. More than 300 volunteers attended Reports by eight solicitation divisions that show the campaign has reached a total of $4,341,149 so far on the way to raising a $6,874,450 goal.” [Credit: Denver Post archives]

|

In 1977, the Coca-Cola Company’s Atlanta headquarters published and distributed complimentary copies of a booklet entitled, “Steps to Success: United Way Firm Campaigning Made Easy.” It was a “one size fits all” manual for United Way workplace fund-raising whose chapters included prescribed, detailed approaches to:

Today, Coca-Cola still satisfies. The fund-raising manual does not.

NOW: Common approaches to fund-raising these days are the exception, not the rule. A universal new approach to fund-raising has yet to emerge, but the Intro in DonorPerfect’s “Guide to Fundraising in the New Normal” offers words everyone can take heart from, as follows:

“Even before COVID-19, your organization was no stranger to the ever-evolving landscape of fundraising. So as you learn new strategies, tailor your communication templates, and take on new tools, do so with the confidence that success will follow. Remember, it’s organizations like yours that showed us the way before COVID-19 and taught us how to give, help, and support those in need during this crisis.”

In its 2019-2020 Impact Report, the United Way Williamson County (now part of the United Way for Greater Austin, Texas) pictured this strategy that has come to pervade current local fund-raising approaches:

- PRE-CAMPAIGN: Recruitment, training, materials, promotion, CEO calls.

- GOAL SETTING

- EVENTS: Kickoffs, Agency tours, Report Meetings, Victory/Appreciation Events.

- PROMOTION

- SOLICITING CONTRIBUTIONS: Corporation, employees, individuals, organizations.

- SAYING “Thank you!”

- EVALUATING approaches, results, and volunteer personnel.

Today, Coca-Cola still satisfies. The fund-raising manual does not.

NOW: Common approaches to fund-raising these days are the exception, not the rule. A universal new approach to fund-raising has yet to emerge, but the Intro in DonorPerfect’s “Guide to Fundraising in the New Normal” offers words everyone can take heart from, as follows:

“Even before COVID-19, your organization was no stranger to the ever-evolving landscape of fundraising. So as you learn new strategies, tailor your communication templates, and take on new tools, do so with the confidence that success will follow. Remember, it’s organizations like yours that showed us the way before COVID-19 and taught us how to give, help, and support those in need during this crisis.”

In its 2019-2020 Impact Report, the United Way Williamson County (now part of the United Way for Greater Austin, Texas) pictured this strategy that has come to pervade current local fund-raising approaches:

A variety of local United Way leaders shared the following “Now” information about their community’s current approaches to fund-raising. They included:

with the exception of summertime “pacemaker” campaigns among a few firms and

the springtime “bell-weather” campaign in Rochester, NY.

NOW: “We run our campaign year-round to meet the various timelines for workplaces.”

“It is continuous. . . .not even called a campaign anymore.”

“The fall continues to be our time of the year for fund-raising, although each year we

start earlier and end later.”

“Year-round fund-raising.”

“The majority of workplace campaigns run August-December with a few outliers.”

“We continue to introduce non-workplace year-round efforts including quarterly

appeals and a sustaining monthly donor program.”

NOW: “Set internally; not reported publicly.”

“Have not announced a goal or fund-raising results in several years.”

“Establish our goal for the year in January. Report in April of the following year.”

“Considered during the summer and announced at the beginning of the campaign.”

“Have not publicly announced a goal in recent years.”

releases, running races, agency presentations and speeches were common.

NOW: “Kickoff in August with media coverage, report meetings, and celebration in March with results.”

“Campaign celebration in April with 250 community partners attending to hear results

and award innovative campaigns.”

“No public kickoff event.”

“Over the past 3-4 years we’ve moved away from public kickoffs.”

“We now license and manage software that allows our partners to run their own special events – auctions, raffles, tickets sales, etc.”

“Public reporting of fund-raising results; regular cabinet and board reports;

celebrations.”

“Multiple public kickoffs and report meetings.”

figures, U.S. President’s endorsement, direct mailing and donated daily newspaper

“double-truck” advertisements were common.

NOW: “We maintain a robust presence on multiple social platforms (Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn) as well as on our YouTube channel. Our goals are to post 50% of posts about our campaign, our donors and partners and 50% on our impact work, our services, and our agency partners.”

“Social media is a large part of our general awareness and partner recognition efforts. In particular, LinkedIn has proven to be a strong engagement platform with our corporate partners and their employee donors.”

“Recognize top corporate supporters and new business lists through social media and in-person events.”

“We have not had Public Service Announcements in recent years but have increased focus on media appearances.”

“Printed campaign brochure.”

“No printed materials.”

“Very little printed material.”

“Use PSAs on TV and purchase radio advertising to drive people to our services.”

“We continue to use PSAs, radio and TV spots, plus social media.”

“We continue to film stories to use in kickoffs and presentations. With creative editing, we can adapt specific stories to corporate and donor interest areas.”

“We have partnered with ‘Yellow Box’ to help with all marketing and communications, including videos that are made available on our YouTube channel with links in social media and on our website.”

“We typically produce an annual video that can be shown in workplace settings and produce a number of shorter videos on specific topics.”

NOW: “Since 2021, we have focused on a much smaller campaign cabinet made up of volunteers with close personal and business relationships to the chair.”

“We use campaign volunteers, but not successfully.”

“Staff relationship managers do most of our fund-raising.”

“Use approximately 30 volunteers plus Board members.”

“Three seasonal ‘campaign coordinators’ are employed to assist with workplace campaigns September-December.” “Can no longer justify the cost of staff support to volunteers so staff are responsible for fund-raising. Some use volunteers to help.”

“We no longer have a Loaned Executive program.”

“We continue to use Loaned Executives.”

“Companies claim they don’t have anyone to be Loaned Executives.”

NOW: “Counting grants, contracts, and foundation grants in the fund-raising total.”

“We use a platform that makes credit card payments and online gifts simple and provides us with a record of donations."

“Card scanning and E-pledge.”

“We combine reports from independent processors with our own records of contributions.”

“Reports shared with Board of Directors as part of regular financial statements.”

“Introduced DonorPoint this year. It is an online campaign platform that allows employees to donate directly from their paychecks, via check or credit card or through gifts throughout the year through ever-green campaigns."

Searching for a “new normal.”

In the September-October 2018 edition of The Harvard Business Review retired United Way Worldwide President & CEO Brian Gallagher wrote, “We’re moving to a technology-driven engagement platform [that] increases our interactions with donors and allows them to become more closely involved in our mission.

DonorPerfect’s Guide to Fundraising in the New Normal notes, “Although the way we come together, communicate, and do - well, just about everything we used to do - is quite different these days. . . Even before COVID-19, your organization was no stranger to the ever-evolving landscape of fundraising. So as you learn new strategies, tailor your communication templates, and take on new tools, do so with the confidence that success will follow.”

Before stepping down from her position as Executive Director of the United Way of Monroe County, Indiana, in 2022, Efrat Feferman spoke for all of us “insiders!” She challenged the people of the Bloomington area. "Let's build a better normal!" she said.

Finally, this sample of a positive “outsider’s” perspective supports the United Way movement’s capacity to adapt to its changing environment. From the February 6, 2024, issue of Forbes in an article entitled, “United Way Looks to the Future” . . .

“Times are tough for many nonprofit organizations. Costs are up; donations are down. Volunteers are staying home, and many charities are looking for new business models to become more sustainable. In the face of these mounting challenges, nonprofits are turning to new, transformational leaders, and forming partnerships with other organizations, corporations, and government entities. . . . . . United Way is experiencing an exciting yet challenging time of transformational growth—working to bring its 135-year-old organization into a new era, and with [Angela] William’s leadership at the helm, it is in a prime position to make positive, long-lasting changes in the world.”

- Melissa Reabold, CEO, United Way of Greater Baytown Area and Chambers County, Baytown, Texas.

- Rodney Prunty, President & CEO, United Way of North Central New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico

- Renee Moe, President & CEO, United Way of Dane County, Madison, Wisconsin

- Mike Baker, Chief Strategy Officer, United Way of Greater Cincinnati, Ohio

- DJ Hampton II, President & CEO, Trident United Way, Charleston, South Carolina

- Several others who wished to remain anonymous.

- Scheduling:

with the exception of summertime “pacemaker” campaigns among a few firms and

the springtime “bell-weather” campaign in Rochester, NY.

NOW: “We run our campaign year-round to meet the various timelines for workplaces.”

“It is continuous. . . .not even called a campaign anymore.”

“The fall continues to be our time of the year for fund-raising, although each year we

start earlier and end later.”

“Year-round fund-raising.”

“The majority of workplace campaigns run August-December with a few outliers.”

“We continue to introduce non-workplace year-round efforts including quarterly

appeals and a sustaining monthly donor program.”

- Goal setting:

NOW: “Set internally; not reported publicly.”

“Have not announced a goal or fund-raising results in several years.”

“Establish our goal for the year in January. Report in April of the following year.”

“Considered during the summer and announced at the beginning of the campaign.”

“Have not publicly announced a goal in recent years.”

- Events:

releases, running races, agency presentations and speeches were common.

NOW: “Kickoff in August with media coverage, report meetings, and celebration in March with results.”

“Campaign celebration in April with 250 community partners attending to hear results

and award innovative campaigns.”

“No public kickoff event.”

“Over the past 3-4 years we’ve moved away from public kickoffs.”

“We now license and manage software that allows our partners to run their own special events – auctions, raffles, tickets sales, etc.”

“Public reporting of fund-raising results; regular cabinet and board reports;

celebrations.”

“Multiple public kickoffs and report meetings.”

- Promotion:

figures, U.S. President’s endorsement, direct mailing and donated daily newspaper

“double-truck” advertisements were common.

NOW: “We maintain a robust presence on multiple social platforms (Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn) as well as on our YouTube channel. Our goals are to post 50% of posts about our campaign, our donors and partners and 50% on our impact work, our services, and our agency partners.”

“Social media is a large part of our general awareness and partner recognition efforts. In particular, LinkedIn has proven to be a strong engagement platform with our corporate partners and their employee donors.”

“Recognize top corporate supporters and new business lists through social media and in-person events.”

“We have not had Public Service Announcements in recent years but have increased focus on media appearances.”

“Printed campaign brochure.”

“No printed materials.”

“Very little printed material.”

“Use PSAs on TV and purchase radio advertising to drive people to our services.”

“We continue to use PSAs, radio and TV spots, plus social media.”

“We continue to film stories to use in kickoffs and presentations. With creative editing, we can adapt specific stories to corporate and donor interest areas.”

“We have partnered with ‘Yellow Box’ to help with all marketing and communications, including videos that are made available on our YouTube channel with links in social media and on our website.”

“We typically produce an annual video that can be shown in workplace settings and produce a number of shorter videos on specific topics.”

- Personnel:

NOW: “Since 2021, we have focused on a much smaller campaign cabinet made up of volunteers with close personal and business relationships to the chair.”

“We use campaign volunteers, but not successfully.”

“Staff relationship managers do most of our fund-raising.”

“Use approximately 30 volunteers plus Board members.”

“Three seasonal ‘campaign coordinators’ are employed to assist with workplace campaigns September-December.” “Can no longer justify the cost of staff support to volunteers so staff are responsible for fund-raising. Some use volunteers to help.”

“We no longer have a Loaned Executive program.”

“We continue to use Loaned Executives.”

“Companies claim they don’t have anyone to be Loaned Executives.”

- Data Management:

NOW: “Counting grants, contracts, and foundation grants in the fund-raising total.”

“We use a platform that makes credit card payments and online gifts simple and provides us with a record of donations."

“Card scanning and E-pledge.”

“We combine reports from independent processors with our own records of contributions.”

“Reports shared with Board of Directors as part of regular financial statements.”

“Introduced DonorPoint this year. It is an online campaign platform that allows employees to donate directly from their paychecks, via check or credit card or through gifts throughout the year through ever-green campaigns."

Searching for a “new normal.”

In the September-October 2018 edition of The Harvard Business Review retired United Way Worldwide President & CEO Brian Gallagher wrote, “We’re moving to a technology-driven engagement platform [that] increases our interactions with donors and allows them to become more closely involved in our mission.

DonorPerfect’s Guide to Fundraising in the New Normal notes, “Although the way we come together, communicate, and do - well, just about everything we used to do - is quite different these days. . . Even before COVID-19, your organization was no stranger to the ever-evolving landscape of fundraising. So as you learn new strategies, tailor your communication templates, and take on new tools, do so with the confidence that success will follow.”

Before stepping down from her position as Executive Director of the United Way of Monroe County, Indiana, in 2022, Efrat Feferman spoke for all of us “insiders!” She challenged the people of the Bloomington area. "Let's build a better normal!" she said.

Finally, this sample of a positive “outsider’s” perspective supports the United Way movement’s capacity to adapt to its changing environment. From the February 6, 2024, issue of Forbes in an article entitled, “United Way Looks to the Future” . . .

“Times are tough for many nonprofit organizations. Costs are up; donations are down. Volunteers are staying home, and many charities are looking for new business models to become more sustainable. In the face of these mounting challenges, nonprofits are turning to new, transformational leaders, and forming partnerships with other organizations, corporations, and government entities. . . . . . United Way is experiencing an exciting yet challenging time of transformational growth—working to bring its 135-year-old organization into a new era, and with [Angela] William’s leadership at the helm, it is in a prime position to make positive, long-lasting changes in the world.”